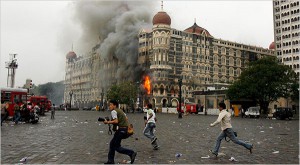

Big Clues Missed in 26/11 Mumbai Terror

WASHINGTON: In the fall of 2008, a 30-year-old computer expert named Zarrar Shah roamed from outposts in the northern mountains of Pakistan to safe houses near the Arabian Sea, plotting mayhem in Mumbai, India’s commercial gem.

WASHINGTON: In the fall of 2008, a 30-year-old computer expert named Zarrar Shah roamed from outposts in the northern mountains of Pakistan to safe houses near the Arabian Sea, plotting mayhem in Mumbai, India’s commercial gem.

Shah, the technology chief of Lashkar-e-Taiba, the Pakistani terror group, and fellow conspirators used Google Earth to show militants the routes to their targets in the city. He set up an Internet phone system to disguise his location by routing his calls through New Jersey. Shortly before an assault that would kill 166 people, including six Americans, Shah searched online for a Jewish hostel and two luxury hotels, all sites of the eventual carnage.

But he did not know that by September, the British were spying on many of his online activities, tracking his Internet searches and messages, according to former U.S. and Indian officials and classified documents disclosed by Edward J. Snowden, the former National Security Agency contractor.

They were not the only spies watching. Shah drew similar scrutiny from an Indian intelligence agency, according to a former official briefed on the operation. The United States was unaware of the two agencies’ efforts, U.S. officials say, but had picked up signs of a plot through other electronic and human sources, and warned Indian security officials several times in the months before the attack.

What happened next may rank among the most devastating near-misses in the history of spycraft. The intelligence agencies of the three nations did not pull together all the strands gathered by their high-tech surveillance and other tools, which might have allowed them to disrupt a terror strike so scarring that it is often called India’s 9/11.

“No one put together the whole picture,” said Shivshankar Menon, who was India’s foreign minister at the time of the attacks and later became the national security adviser. “Not the Americans, not the Brits, not the Indians.” Menon, now retired, recalled that “only once the shooting started did everyone share” what they had, largely in meetings between British and Indian officials, and then “the picture instantly came into focus.”

The British had access to a trove of data from Shah’s communications, but contend that the information was not specific enough to detect the threat. The Indians did not home in on the plot even with the alerts from the United States.

Clues slipped by the Americans as well. David Coleman Headley, a Pakistani-American who scouted targets in Mumbai, exchanged incriminating emails with plotters that went unnoticed until shortly before his arrest in Chicago in late 2009. U.S. counterterrorism agencies did not pursue reports from his unhappy wife, who told U.S. officials long before the killings began that he was a Pakistani terrorist conducting mysterious missions in Mumbai.

That hidden history of the Mumbai attacks reveals the vulnerability as well as the strengths of computer surveillance and intercepts as a counterterrorism weapon, an investigation by The New York Times, ProPublica and the PBS series “Frontline” has found.

Although electronic eavesdropping often yields valuable data, even tantalizing clues can be missed if the technology is not closely monitored, the intelligence gleaned from it is not linked with other information, or analysis does not sift incriminating activity from the ocean of digital data.

This account has been pieced together from classified documents, court files and dozens of interviews with current and former Indian, British and U.S. officials. While telephone intercepts of the assault team’s phone calls and other intelligence work during the three-day siege have been reported, the extensive espionage that took place before the attacks has not previously been disclosed. Some details of the operations were withheld at the request of the intelligence agencies, citing national security concerns. “We didn’t see it coming,” a former senior U.S. intelligence official said. “We were focused on many other things – al-Qaida, the Taliban, Pakistan’s nuclear weapons, the Iranians. It’s not that things were missed – they were never put together.”

After the assault began, the countries quickly disclosed their intelligence to one another. They monitored a Lashkar control room in Pakistan where the terror chiefs directed their men, hunkered down in the Taj and Oberoi hotels and the Jewish hostel, according to current and former U.S., British and Indian officials.

That cooperation among the spy agencies helped analysts retrospectively piece together “a complete operations plan for the attacks,” a top-secret NSA document said.

The attacks still resonate in India, and are a continuing source of tension with Pakistan. Last week, a Pakistani court granted bail to a militant commander, Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, accused of being an orchestrator of the attacks. He has not been freed, pending an appeal. India protested his release, arguing it was part of a Pakistani effort to avoid prosecution of terror suspects.

Lashkar’s Computer ChiefZarrar Shah was a digitally savvy operative, a man with a bushy beard, a pronounced limp, strong ties to Pakistani intelligence and an intense hatred for India, according to Western and Indian officials and court files. The spy agencies of Britain, the United States and India considered him the technology and communications chief for Lashkar, a group dedicated to attacking India. His fascination with jihad established him as something of a pioneer for a generation of Islamic extremists who use the Internet as a weapon.

According to Indian court records and interviews with intelligence officials, Shah was in his late 20s when he became the “emir,” or chief, of the Lashkar media unit. Because of his role, Shah, together with another young Lashkar chief named Sajid Mir, became an intelligence target for the British, Indians and Americans.

Lashkar-e-Taiba, which translates as “the Army of the Pure,” grew rapidly in the 1990s thanks to a powerful patron: the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI), the Pakistani spy agency that the CIA has worked with uneasily for years. Lashkar conducted a proxy war for Pakistan in return for arms, funds, intelligence, and training in combat tactics and communications technology. Initially, Lashkar’s focus was India and Kashmir, the mountainous region claimed by both India and Pakistan.

Leaving a Trail

Not long after the British gained access to his communications, Shah contacted a New Jersey company posing online as an Indian reseller of telephone services named Kharak Singh, purporting to be based in Mumbai. His Indian persona started haggling over the price of a voice-over-Internet phone service – also known as VoIP – that had been chosen because it would make calls between Pakistan and the terrorists in Mumbai appear as if they were originating in Austria and New Jersey.

“its not first time in my life i am perchasing in this VOIP business,” Shah wrote in shaky English, to an official with the New Jersey-based company when he thought the asking price was too high, the GCHQ documents show. “i am using these services from 2 years.”

Shah had begun researching the VoIP systems, online security, and ways to hide his communications as early as mid-September, according to the documents. As he made his plan, he searched on his laptop for weak communication security in Europe, spent time on a site designed to conceal browsing history, and searched Google News for “indian american naval exercises” – presumably so the seagoing attackers would not blunder into an overwhelming force.

Ajmal Kasab, the only terrorist who would survive the Mumbai attacks, watched Shah display some of his technical prowess. In mid-September, Shah and fellow plotters used Google Earth and other material to show Kasab and nine other young Pakistani terrorists their targets in Mumbai, according to court testimony.

If Shah made any attempt to hide his malevolent intentions, he did not have much success at it. Although his frenetic computer activity was often sprawling, he repeatedly displayed some key interests: small-scale warfare, secret communications, tourist and military locations in India, extremist ideology and Mumbai.

By Nov. 24, Shah had moved to the Karachi suburbs, where he set up an electronic “control room” with the help of an Indian militant named Abu Jundal, according to his later confession to the Indian authorities. It was from this room that Mir, Shah and others would issue minute-by-minute instructions to the assault team once the attacks began. On Nov. 25, Abu Jundal tested the VoIP software on four laptops spread out on four small tables facing a pair of televisions as the plotters, including Mir, Shah and Lakhvi, waited for the killings to begin.

In a plan to pin the blame on Indians, Shah typed a statement of responsibility for the attack from the Hyderabad Deccan Mujahadeen – a fake Indian organization. Early on Nov. 26, Shah showed more of his hand: He emailed a draft of the phony claim to an underling with orders to send it to the news media later, according to U.S. and Indian counterterrorism officials.

A Trove of Data

In the United States, Nov. 26 was the Wednesday before Thanksgiving. Anish Goel, director for South Asia at the National Security Council in the White House, left around 6 a.m. for the 8-hour drive to his parents’ house in Ohio. By the time he arrived, his BlackBerry was filled with emails about the attacks.

The Pakistani terrorists had come ashore in an inflatable speedboat in a fishermen’s slum in south Mumbai about 9 p.m. local time. They fanned out in pairs and struck five targets with bombs and AK-47s: the Taj, the Oberoi Hotel, the Leopold Cafe, Chabad House, and the city’s largest train station.

“Analysis of Zarrar Shah’s viewing habits” and other data “yielded several locations in Mumbai well before the attacks occurred and showed operations planning for initial entry points into the Taj Hotel,” the NSA document said.

Amid the crisis, Goel, now a senior South Asia Fellow at the New America Foundation, paid little attention to the sources of the intelligence and said that he still knew little about specific operations. But two things stood out, he said: The main conspirators in Pakistan had already been identified. And the quality and rapid pacing of the intelligence reports made it clear that electronic espionage was primarily responsible for the information. “During the attacks, it was extraordinarily helpful,” Goel said of the surveillance.

But until then, the United States did not know of the British and Indian spying on Shah’s communications. As NSA and GCHQ analysts worked around the clock after the attacks, the flow of intelligence enabled Washington, London and New Delhi to exert pressure on Pakistan to round up suspects and crack down on Lashkar, despite its alliance with the ISI, according to officials involved.( The New York Times News Service)